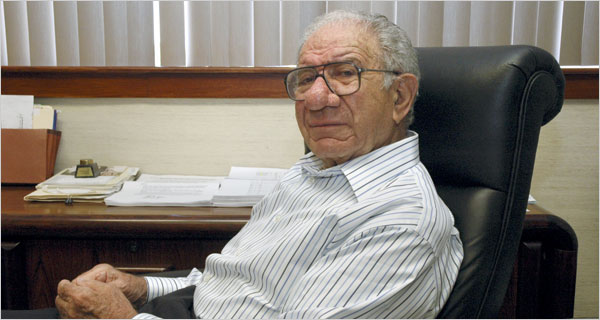

IN early October, Michael J. Hogan was still in his first weeks as president of the University of Connecticut, but he already knew pertinent facts about the 85-year-old developer and philanthropist sitting at his lunch table.

He was aware that Simon Konover was a major benefactor of the university and that he and his wife, Doris, would soon deliver a $1.5 million gift endowing UConn’s first faculty chair in Judaic Studies. He had also been briefed about Mr. Konover’s other charitable work: that he had built Paul Newman’s Hole in the Wall Gang Camp without charging a fee, for example; and that he had been a major force in the creation of the United States Holocaust Museum in Washington.

What President Hogan did not know was that Mr. Konover, while enjoying pasta salad with goat cheese, had allowed himself a private memory. He thought back nearly six decades to when, as a laborer, he laid flooring for the university’s new dormitories.

Mr. Konover recalled other images, and concluded that for a man who had never finished high school, and who could easily have been killed many times, and who endured what no son of devoted parents should have to endure, he had been blessed.

He later told me: “It’s a miracle I’m even here. If you would tell me years ago I would have a normal life with children, grandchildren and great grandchildren, I’d say you must be out of your mind.”

Stories of the Holocaust are both abundant and endangered. Survivors like Mr. Konover are compelled to tell them because of Holocaust denial and the ticking of the clock, leading us to a time when no witness will be around to add testimony.

Mr. Konover’s story begins with him growing up with six brothers and sisters in a shtetl in the Polish town Makow Mazowiecki. He didn’t know the seventh and oldest sibling, David, who had gone off to America the year Simon was born. Their father delivered flour by horse and wagon to Warsaw, an overnight trip, and brought merchandise back — until the day in 1939 when a 16-year-old Simon watched German soldiers and panzers parade into town, and heard the announcement by bullhorn: “Stay indoors. If you go outside, you will be shot.”

When teenage boys were ordered to report to the market square, Simon was given the job of cleaning up sewage, then sent to a nearby labor camp. After two weeks, he and seven others tried a daring escape beneath barbed wire. Five were gunned down. Simon made it home, and the next day, when the Nazis came knocking, he hid beneath wood in the cellar, listening to the sound of jackboots above.

Afterward, his parents, terrified that his pursuers would return, told Simon that he would have to find refuge with relatives, including an older brother, Harold, by then in eastern Poland. They gave him provisions and sent him off with a younger brother, Chaim. Simon, who had never been away from home except to Warsaw with his father, cried every day. Chaim, homesick, quit the journey to go back. It was the last time they saw each other.

The odyssey that followed found young Simon almost always hungry and cold, sleeping on floors, getting odd jobs, fearful of the advancing German Army. He indeed hooked up with Harold, who “was like a father to me.” Eventually, the two wound up in Stalingrad, where “anybody who could walk” was drafted into the Soviet Army, and where Simon drove trucks.

There, a bad break saved his life. After a night of carousing, Simon was charged with disobeying orders and sentenced to three years of hard labor in Siberia. Had that not happened, he would have been assigned to drive in a convoy that was wiped out by German fighter planes.

When the war ended, he was released and given permission by the Soviets to go look for his family. But he soon learned that all 6,000 of his town’s Jews were gone.

Decades later, he started talking about the Holocaust, “because some people say it never happened.”

“If it never happened,” he said, “where are my parents, my sisters, my brothers?”

Mr. Konover and Harold eventually made it to America with the help of David, their brother who had left Poland early. David owned a flooring company, and he put Simon to work. From there, it was all upward — as a supervisor, then starting his own companies in West Hartford. During his career, he has built more than 100 shopping centers, as well hotels, office buildings and apartments.

The secret of his success? “There are a lot of people in business who are smarter than I am,” he says, but few who have learned what he has learned.

Not every competitor can separate real crisis from perceived crisis. If Mr. Konover runs into a difficult condominium market — as he has recently — he doesn’t panic. He has experienced far worse than falling housing prices. Work, after all, is only a matter of profit and loss. It isn’t the stuff of jackboots, bullhorns and murderers.

It is work — which he intends to do “until I die” — that keeps him from thinking too much about the past, about how “my mother and father went to the ovens without knowing whether Harold and I were alive.”

He adds, “If I am able to make more money, I’ll be able to give more away.”

Click here to read the original New York Times Article